It is difficult to describe what Sejla Kameric’s work is about. It is about an international conflict (the Balkan wars). It is about the decline of a city (Sarajevo). It is about ethnic cleansing (of Bosnian-Herzegovians). It is about longing for a past that is lost (a culture’s, a city’s, the artist’s). It is about the emancipation of a young girl (the artist herself). Kameric’s work is political. But it is also personal. However, one would be mistaken to call the political personal and vice-versa.

One might be tempted to argue it is about deconstruction. Works such as EU/Others (2000) and Bosnian Girl(2003), which examine the relationship between representation and subjectivity, would certainly vindicate such an assertion. But then one might also suggest it is about reconstruction. The piece Dream House (2002), for instance, situates a refugee camp within parameters that place it beyond its conventional confines. The camp’s spacetime transits from sunset into sunrise, transforms from desolate desert to desirable beach. The work thus constructs the impossible possibility of an elsewhere beyond the now-here.

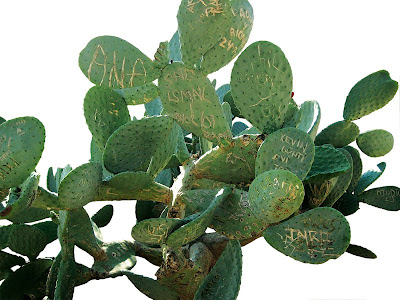

Similarly, one may feel Kameric’s work is concerned with the past. After all, many of her works address traumas and memories. Yet one cannot but feel it is equally preoccupied with the future. In Red (2008) Kameric seeks to trace what is lost. She traces marks on red brick walls left by explosive devices. In Green (2007) she tries to find expressions of what cannot be expressed. She photographs names carved in cactuses. Each act emphasizes what cannot be regained. Each act emphasizes that every attempt will leave its imprints, or, in the example of the plants, literally, its scars. But it also stresses that one should attempt nonetheless. For it is in the act that we can find something we had not found before: a trace of a past and a hint of a future, a memory of those we loved and a dream to love them again.

One may deem Kameric’s work an interrogation of collective identity. But it is certainly also a quest into individual idiosyncrasies. It is conscious of local traditions, but aware of the global inevitabilities. If it is alienating, it is also adamant on coming to terms with one’s position.

Anselm Wagner writes:

In Sejla Kameric the dream and the trauma seem to be causally connected. She channels the pain in two quite different directions: into a biting, almost cynical criticism of political conditions and, at the same time, into a longing escapism (…) Kameric works against current clichés about victims (poor, desperate, submissively seeking help, etc.), because they only serve to produce a permanent condition of dependency, so that the ‘helpers’ can extend their position of power. At the same time, however, Kameric does not pose in the heroic role of an angry member of the resistance (which is just another cliché, even if it comes from a difference political direction). Rather, she insists on being permitted to be a dreamer, who is sometimes happy to shut her eyes to reality, who is vulnerable, who is sad, who is homesick for a Sarajevo that is more than merely a synonym for ‘breaking news’ and for a murderous war against civilians.

What Wagner unearths in Kameric’s work, is an oscillation between two modes of existence: cynicism and pathos, knowingness and naivety, fear and fearlessness, the victim and the revolutionary. I am inclined to say that the frightened victim is the figure of the postmodern. The fearless revolutionary, indeed, is the embodiment of the modern. The dreamer is both of them. Yet it is also neither of them. The dreamer believes in the potential of each, but realizes it cannot enact them in full. It believes in a future beyond its grasp.

Images: Selja Kameric, What Do I Know (2007) and Green (2007). Courtesy Galerie Tanja Wagner